Share this:

Locked!

It's Friday morning, November 24. Together with my friend Anton, I'm getting ready for our annual mountain adventure. Every autumn, we spend a few days in the mountains. Sometimes they're still green, occasionally fairly white, and often somewhere in between. This autumn seems to follow that pattern. Normally, I spend several days a week in the mountains, for work or leisure. But after a family visit in the Netherlands, the constant rain shifted my focus to chores instead of mountain adventures. Consequently, I don't have a clear idea of what we'll encounter higher up, especially regarding the amount of snow.

What could possibly go wrong?

The chore focus also meant I didn't prepare for this trip as thoroughly as I usually do. The rough plan is to hike from the Arve valley to the Giffre valley over a 3-day trek, using snowshoes where needed. Under the motto of "what could possibly go wrong," Anton and I venture into this adventure. To reach the starting point, we decide to use public transportation. First, by train to Sallanches and then with the new bus service to Plaine Joux at 1300m. In our rush to catch the train, I realize I left a hiking stick in the car. Both of us are equipped with sturdy backpacks, so the sticks are necessary. Our first mission is to find a suitable stick.

A warm and pleasant start

Around noon, we set off, the weather is fantastic, and soon we're hiking in our T-shirts. An hour later, we reach the tree line, which also marks the snow line. It's lower than I expected, and there's so much snow that we strap on our snowshoes after the picnic. It's not a problem per se, but it does slow our progress. From 1700m, there's a continuous snow cover, which we have to break through since our telescopic poles are still in summer mode. Forgetting to put the discs on your poles is a typical case of not being winter-ready. When we were in the Netherlands two weeks earlier, there was heavy snowfall. So much so that many local friends had their first ski/splitboard tour already planned. Then it became very warm, causing avalanches on many steep slopes. Consequently, we cross several debris zones with large snow chunks. The good news is that the avalanche danger is no longer current. Either the snow has completely melted, or it's so old and frozen that it won't slide anymore. Fortunately, this reality matches the image I had formed of these 35+ degree slopes beforehand. Based on this expectation, I deemed it responsible to undertake this trek. The weather forecast for day two has changed frequently in the past few days. The sun was expected to show up occasionally, but there's also a prediction of 5 to 10cm of snow. I considered this amount insufficient to change our plan; what could possibly go wrong?

No, it's locked!

Around 4:30 pm, we pass the steepest and most challenging part of day one, but there's not enough snow here to make it really challenging. It's starting to get dusk, our legs are getting heavier, and we're looking forward to the hut. I feel a bit stressed. We've used this shepherd's hut a few times before, and the door used to be open. But after some negative experiences, the owner decided to lock it. However, our guide friend Serge told me last winter that the hut was accessible again. Before we venture here mid-winter with a touring group, I thought it would be a good opportunity to verify the hut with Anton. As a precaution, we have all the gear to build a (snow) shelter. When we arrive at the hut, to our shock, we see a thick lock on the door. We stand there, puzzled; we're tired, it's already dark, and it's getting significantly colder. We check the surrounding huts. Unfortunately, we find no open doors but spot an option for a snow shelter between two roofs.

Then Anton points to a window about 4 meters high, and yes, I remember it from the time we slept here, considering it as an option if there was too much snow blocking the entrance! I immediately climb onto the roof and can just reach the small sliding window from the ridge. Yes, it's open! But how do you enter a window 4 meters high? Without hesitation, we decide to build a ladder. An hour and a half later, there's a one and a half-meter-high snow ladder. On top of this, we place a backpack and hoist ourselves through the small window. We're in! Barely recovering from the initial shock, we discover that we have to descend another 4 meters! I dare say this was the 'crux' of the day! But we tackle this challenge too, and a little later, tired but satisfied, we lie in our down sleeping bags on the musty yellow foam mattresses in a room that barely passes for a bedroom. At a room temperature of minus 1, enjoying our packed meal, the astronaut meal, and a glass of wine. Joseph and Mary might have searched a bit longer, but Anton and Arno are as happy as can be.

It's dumping!

The next morning when we wake up, we have no idea what it looks like outside. There's no window to look out of, and our entrance is (almost) unreachable. We take it easy, knowing we have the whole day to reach our next destination. During breakfast, we discuss the plan for today. The idea is to climb from the hut at 1880m via a long zigzag route to the ridge-line at 2480m and then descend to Refuge d'Alfred Wills at 1800m. Plan B is to partially hike back from where we came, pass halfway through the summer col, and still head towards the refuge. After stretching, we're ready for our escape. I climb up, push open the window, and stick my head out. It remains silent for a moment, then I report to Anton: "It's snowing, and there's at least 25cm of fresh snow around the hut...." Immediately, my brain goes into risk assessment mode, and I mentally fill in Werner Munter's 3x3 grid: How much snow has fallen, what was the temperature, has it been windy, can we stay away from 35+ degree slopes, how is our mental and physical condition? What's certain is that this snowpack will slow us down significantly and, worse, might bring avalanche danger. I briefly doubt whether I did the right thing but decide to share my concerns with Anton, including the fact that plan B is no longer an option since it would mean constantly walking under a steep and potentially avalanche-prone slope. This confirms the choice for plan A.

Off we go

After some stretching excercises we feel ready to face the climb out of our safe shelter. We refill our camelbags from the stream and set off. I recall the route we walked on snowshoes here before and opt for the same starting point. After half an hour, we get stuck. The freshly fallen snow is light and has fallen on a hard layer of icy snow. As it gets steeper, the snowshoes lose grip, and traversing becomes practically impossible. On my digital map, I see a section that seems too steep, prompting us to turn back to where we came from. The passage above the hut feels slightly too steep, but we don't have another choice. It keeps snowing, visibility is poor, and we progress painfully slowly. With each step upward, we slide back half a step, a whole step, and sometimes even a step and a half. By noon, we're only at an altitude of 2000m. Despite the poor visibility, navigation goes well. On my digital map, I scan slopes steeper than 30 degrees and make sure we stay away from those. On a tricky passage, my found stick breaks. I consider continuing with the remaining part, but then I spot a clump of willows. The ten meters to reach it are steep and icy, but since we're at 2000m, this might be the last little tree on our route upwards. With my Rambo knife, I cut off a thick and straight piece and, happy with my new stick, reunite with Anton. We have no time for lunch and sustain ourselves with Snelle Jelles (or Vlugge Japies?) and take turns biting into a thick Savoyard sausage.

The snow get's deeper and deeper

Midway through the climb, we're surprised by a couloir starting from a waterfall, not marked on my map. Steep areas along mountain streams are notorious for weak snow layers, and the fresh snow here has already piled up to 40cm. I feel a moment of despair, "Shit Toine, I don't know what to do anymore!" I start worrying about the time it's taking us and the continuing poor visibility. The snowpack gets deeper and deeper on a slope perfect for skiing or snowboarding but too steep for climbing with snowshoes. Fortunately, Anton still has full confidence and encourages me to stay positive and keep going. Meanwhile, my phone is almost out of battery. I'd rather ignore the red light, but I know that if it shuts down and restarts, there's a high chance the map won't reload. The Iphiginie app has proven itself more than ever today. We stop, grab the power bank from the bag, and make the only right decision: charge it!

Reaching the crux

Now we've reached the plateau at the foot of our last steep climb, today's crux. As Anton tries to drink some water, his tube has come loose. His entire drinking bag has leaked into his bag! Fortunately, the damage is limited, but to prevent further issues, we put all his belongings in the waterproof bivy bag. In case we end up spending the night in a snow shelter, dry gear becomes crucial. And off we plod again. Suddenly, I hear my phone giving a signal; reception! I seize the opportunity to open Fatmap and study the final climb once more. Just like a few years ago, I conclude that there's actually only one possible route. And then something happens that I'd hoped for all day: it clears up a bit. Finally, we see where we are; completely alone in a deserted white mountain world. And immediately, we notice how steep the final climb is and that my intended route is littered with large chunks of avalanche debris. Forty centimeters of fresh snow (on a thirty-seven-degree slope) is one of the five avalanche alarm signals. But the good news is that we haven't observed the other four: there's no (sign of) wind, we haven't seen recent avalanches, no shooting cracks or whoomp sounds, and there's no sudden warming. And although walking on snowshoes is uncomfortable, the new snow seems to bond well with the hard old base layer. We encourage each other and run through the procedure again of what to do if one of us triggers an avalanche. Allez, let's go.

Will a staircase safe us again?

The avalanche debris provides a sort of natural staircase, and the largest block in the middle of the slope is our beacon that we're aiming for. Oddly enough, this ice block even serves as a safe zone to catch our breath. I try to reassure Anton (and secretly myself) that this avalanche slid in a completely different scenario than today. Three-quarters up the climb, we reach the steepest part. The snowshoes slide again on the icy base, and our energy levels aren't what they used to be. Slipping here would be bad news, so I shout to Anton that every step must count now. Twenty-five meters from the top, this is easier said than done. Because I fear one of us might slip, I decide to take off my bag and grab my shovel. Yesterday, a shovel brought us to safety, and today it needs to happen again. I dig a step into the hard base layer; one chop vertically, one chop horizontally, and hop, gain another half a meter. Twenty steps higher, we face the final obstacle: a two-meter-high cornice (snow overhang). When I later ask Anton what he thought when he saw this, he said, "After everything we've been through and overcome, I had full confidence that you'd figure this out too." Looking back, I think Anton's unwavering trust gave me the self-confidence to keep going. My friend and coach Cees would define this as confidence in your own craftsmanship and mastery. With my last bit of strength, I hack our way through the cornice, and two steps later, we're on our peak; literally and figuratively.

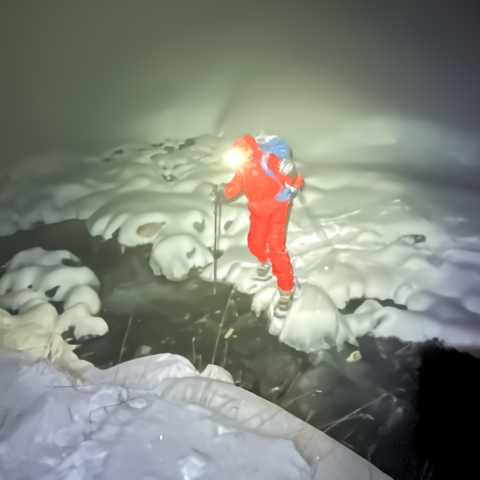

Down in the dark

It's already five o'clock, and dusk is setting in. For a moment, we have a view and see where we came from. What an adventure and what a mental and physical effort it took. We hug each other, crying, letting our emotions flow freely; what a relief! Evening falls, and the visibility closes again. How special that we had sufficient visibility at the most crucial moment of the day?! We still have at least two hours of hiking ahead of us, but now nothing can go wrong anymore. I've descended this path before on snowshoes (and slid on my backpack) and once snowboarded down on my splitboard. The slope angle is everywhere below 30 degrees, and there are hardly any rocks (walls). Strangely enough, there's only about 15 to 20cm of snow here. The descent goes smoothly, and just before seven, we arrive at the refuge. Luckily, it's open! Inside, it's freezing cold. Wrapped in blankets, we silently eat our dry food with a glass of wine. There's little energy left to talk, and we're both in a moment of processing; what an adventure we've been through these past two days!

Bluebird

The next morning is clear and cold. We opt for the longer, safer route back to the car. We look forward to warming up in the November sun, but it seems we're too early. The sun highlights the mighty Rochers des Fiz, but we can only gaze at them. Just like the large herd of ibexes startled by this rare human presence. This part of Haute Savoie is popular and busy in summer, but as soon as winter arrives, it becomes completely isolated. Because we've chosen a different route, we have to climb another 200 meters to reach the car. The plan was to arrive at noon, and almost stumbling, we arrive almost exactly at midday. Our feet feel frozen, but our hearts are warm; we made it!

Mountains speak, wise men listen

We have been living in the French Alps for 16 years now, and for the last 10 years, I've had the privilege of calling this environment my 'office' as a certified mountain leader. During this time, I've initiated and organized numerous Alpine adventures, all based on well-thought-out plans. With proper preparation, you can mitigate risks and prepare for the unexpected. That's what I find so beautiful about the mountains; even with thorough preparation, you can still be surprised by unforeseen obstacles that you have to overcome. It's a constant process of making plans, adjusting, anticipating, improvising, and making choices. In our daily lives, we often have (false) feelings of control, but in the overwhelming mountains, we realize that nature holds the reins, and we, as humans, are merely small and vulnerable cogs. As John Muir ones spoke: "mountains speak, wise men listen."

Some reflections

Of course, you start questioning yourself: If I had known that there would be 40cm of snow, would I have taken Anton with me? Was it wise to head to a hut that might have been locked? Should I have prepared better for this journey? This three-day trek was a perfect example of 'Adventure starts where the plan ends.' And when such an adventure ends well, it strengthens friendships and provides countless beautiful lessons about the mountains and life. Above all, I am proud of Anton, and I found his spirit and trust very inspiring. I also realize once again how valuable, and sometimes even vital, it is to ensure thorough preparation, ideally for me with the help of Werner Munters 3x3 method. But regretting going on this adventure together? Haha; what do you think?

Fearless Forward podcast

In Jan'25 I had the honour to be Sally-Anne's first invite in her new "Fearless Forward podcast series. During our 45mnts chat, we are reflecting on this challenging adventure, to find out how Anton and me got through it.